By Norman Del Mar- On 18th May 1911 Gustav Mahler died of overwork and a strained heart at the age of only fifty-one. Strauss's comment, if terse, reveals an unexpected depth of sympathy: "Mahier's death has affected me greatly," he wrote; "now you'll see even in Vienna he'll be a great man". The characteristic dig at the Viennese musical world refers to Mahler's eventual departure from the Court Opera, which as Director and Conductor-in-Chief he had raised to unprecedented heights, though not without making many enemies.

Yet much as Strauss revered Mahler's standing as an executant, he entirely failed to understand the importance of his creative work. As he later said to his colleague Fritz Busch in typical Bavarian dialect: 'So Busch, der Mahler, dos is iiberhaupt gar ka Komponist. Dos is blos a ganz grosser Dirigent' (That's really no composer at all. Just a very great conductor.) Characteristic as this is of Strauss's attitude, it is also typical of the pre-vailing view of Mahler at that time. Max Reger used almost the same words when talking to Busch. -To some extent the cause for this lay in the quasi-amateur time-table of Mahler's creative outbursts. His career as a composer could never be pursued except during the brief intervals between his regular seasons in intense interpretative and administrative work which his conducting career inevitably carried with it. To the end Mahler greatly resented the fact that life had made of him a mere holiday composer, he to whom composition had in fact always been the very religion of his existence. As a result every new work became a confession of faith, an outpouring of his soul the importance of which it would be impossible to exaggerate. To have tossed off a minor work, let alone to note-spin without care or conviction, would have represented a form of blasphemy, apart from the excruciating waste of priceless time.

It would perhaps be unfair to overstress the extravagant contrast of this passionate, desperate dedication with Strauss’s methodical but un—fussed approach to his creative output. His career had developed with such ease, both as conductor and composer, that he had at an early age taken his artistic gifts for granted, to be exercised regularly and auto—matically. He himself compared his need to compose to that of a cow giving milk. It was not in his nature to fight too strenuously during his tenure of office in this opera house or that, with one orchestra or another, to the detriment of his daily ritual of turning out so many impeccably neat pages of score at the specially designed curved writing desk in his elegant music-room. Nor could this work itself be allowed to be interrupted merely because there was no very interesting project on hand.

It is thus not hard to understand how he came in the meantime idly to sketch out an orchestral fantasy on the subject of the beautiful mountains amongst which he had so recently built the luxurious villa which was to be his home for the rest of his life. Such a conception was no new one; Strauss had long before had the idea for it after a boyhood experience of mountaineering during which the party lost its way during the ascent, while on the return they were overtaken by a storm and drenched to the skin. Writing to his friend Ludwig Thuille at the time of the adventure he had said how extremely interesting he had found it, that he had at once set down his impressions onto the piano, and that ‘naturally it had conjured up a lot of nonsense and giant Wagnerian tonepainting.’

Again in 1900, shortly after the completion of Heldenleben, he was writing to his parents of a symphonic poem which was slumbering deep in his breast, ‘which would begin with a sunrise in Switzerland. Otherwise so far only the idea (love tragedy of an artist) and a few themes exist.’

Yet when he came to address himself seriously to the Alpensinfonie, it had become hardly more than a diversion, Strauss going so far as to make the well-known comment already quoted— that work on it amused him even less than chasing maybugs. He toyed with it only intermittently and but for the war it is conceivable that he would never have bothered to finish it at all. Even so palpable a time-marker as Josephslegende was able to interrupt its progress with the result that composition was spread over four years, from 1911 to February 1915.

Nevertheless, once his mind was made up to go ahead in earnest, he managed to enjoy it and in the end progress was quick. The orchestration, begun on 1st November 1914 and completed in little over three months, can scarcely have presented any serious problems to Strauss, for all its complexity and the extremes of compass he employs for most of the instruments. Gone are the light touches and chamber orchestral textures of Rosenkavalier and Bourgeois Gentilhomme. Gone too are the technical extravagances and wild experimentation of Till and Elektra. ‘At last I have learnt to orchestrate’, he said at the Generalprobe, and sadly one acknowledges that the piece cannot fail to sound securely warm and mellifluous. At the same time the curious blending of the large orchestral forces has a colour all its own which is undeniably apt for the subject matter of the work.

Although once more entitled a Symphony, it is far less so even than its predecessor, the Sinfonia Domestica. There are some twenty—two continuous sections, all carefully labelled in the score, which follow the thesis of the work covering twenty-four hours from night to nightfall in the life of a mountain and its successful assailants. As in Heldenleben, these sections can, with an effort of ingenuity, be grouped together to simulate a gigantic Lisztian symphonic form, with elements ofintroduc— tion, opening allegro, scherzo, slow movement, finale and epilogue; but the lasting impression remains of a free descriptive fantasia, more concerned with graphic pictorialism than of adherence to a formal outline. The following list gives in full the scheme of the work:

- Naclit - Night

- Sonnenaufgang - Sunrise

- Der Anstieg - The ascent

- Eintritt in den Wald - Entry into the wood

- Wanderung neben dem Bache - Wandering by the side of the brook

- Am Wasserfall - At the waterfall

- Erscheinung - Apparition

- Auf blumige Wiesen - On flowering meadows

- Auf der Aim - On the alpine pasture

- Durch Dickicht und Gestrupp auf Irrwegen - Through thicket and undergrowth on the wrong way

- Auf dem Gletscher - On the glacier

- Gefahrvolle Augenblicke - Dangerous moments

- Auf dem Gipfel - On the summit

- Vision - Vision

- Nebel steigen auf - Mists rise

- Die Sonne verdiistert sich - The sun gradually becomes obscured

- Elegie - Elegy

- Stille var dem Sturm - Calm before the storm

- Gewitter uncl Sturm, Abstieg - Thunder and Tempest, descent

- Sonnenuntergang - Sunset

- Ausklang - Waning tones

- Naclit - Night

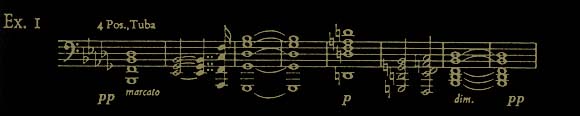

The Symphony opens in deepest night on a unison B flat from which a scale slowly descends, each note as it is sounded sustaining until every degree of the scale is heard simultaneously. No sooner is this opaque mass of string tone established, than a solemn chordal motif is delivered by the heavy brass:

It is not hard to trace the origins of this Wagnerian theme in Strauss's music from as far back as Aus Italien via the ‘Bund’ theme from Guntram, Kunrad’s motif in Feuersnot, and Orestes’ in Elektra. It is also immensely typical in its sudden change of tonality in the middle against wbich the sustained notes of the B flat minor scale persist relentlessly, an instance of polytonal effects rarely to be found in Strauss’s music outside Salome and Elektra.

After this basic presentation of the mountain, massive and imposing in all its stern majesty, Strauss concems himself for a time with background murmurings and shadowy scales over a long tonic pedal (1).

(1) In order that the wind instruments should be able to sustain these long pedal points Strauss recommends the employment of ‘Samuel’s Aerophon’. This alas long-extinct device seems to have supplied oxygen to the distressed player by means of a foot-pump with a tube stretching up to the mouth.

Fragments of Ex. 1 appear on the wind and brass as the complex orchestration gradually builds up to a glowing climax depicting sunrise over the Alps. Inevitably one’s mind is cast back to the previous occasion on which Strauss began a tone-poem with a pictorial demonstration of a mountain sunrise—in Zarathustra. If the earlier example was more dramatically striking, the latter excels in respect of realism. We shall see again and again in the Alpensinfonie Strauss’s curiously detached attitude to the Nature subject of this last of his tone-poems, giving it a de—humanized majestic quality reminiscent, in a unique way, of Bruckner.

Motivically this Sunrise section is based on the descending scale of the Symphony’s opening, though transformed into a melodic outburst:

and followed by a new theme of rich, generous sonority:

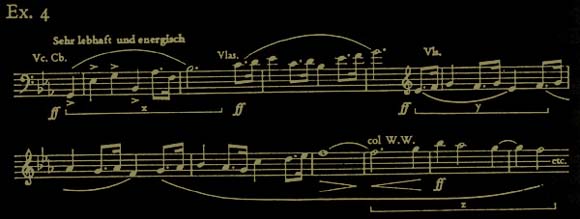

There is a further brief build—up, the orchestra cuts off abruptly, and with the entry of the main marching theme on the lower strings and harp the work passes from the introduction to the first allegro proper.

This is worked out in a full symphonic sentence suggesting the climbing party as they set forth vigorously on the lower slopes. The shape of the theme, Ex. 4, is reminiscent both of the coda from the finale of Beethoven’s C Minor Symphony and of the mountain horn-call in the first Nocturne of Mahler’s Seventh Symphony. Even the treatment is not dissimilar to the latter, though Mahler avoids the jauntiness which is one of the more noticeable characteristics of Strauss’s manner. This particular symphony of Mahler’s is often considered as coming nearest in style to the work of Strauss and there is little doubt that Strauss, for his part, knew this period in Mahler’s output. Moreover, such thematic similarities to the music of other composers continue to occur during the course of the work and are perhaps due to Strauss’s regular appearances as conductor at this time.

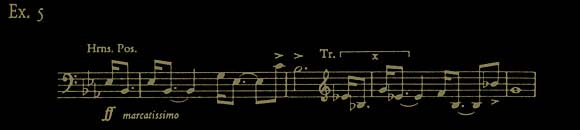

The section comes to a full cadential close which is followed immediately by a triumphant fanfare:

Despite its declamatory first statement, suggesting perhaps the impact upon the climbers of the magnificent rugged scenery around them, Ex. 5 is developed in a manner showing that it refers also to the sheer climb itself, especially with respect to its more arduous and dangerous aspects.

Hunting horns are heard in the distance, represented by an off-stage orchestra of twelve horns together with a pair each of trumpets and trombones (2). The fanfares are wholly non-motivic and neither the hunting horns nor their phrases are heard again throughout the work.

(2) Huge as Strauss’s orchestra undoubtedly is, this apparently grotesque extravagance (a total of twenty horns, including the eight in the orchestra) is in fact less a sign of increasing unreasonable demands in his symphonic instrumentation than of Strauss’s preoccupation with the Wagnerian opera house and the resources he could there take for granted. Tannhauser and Tristan, for example, both call for twelve off-stage horns, while Lohengrin employs not only twelve off-stage trumpets but a further twenty-four instrumentalists for various ensembles of wind and percussion. The Alpensinfonie in fact throws an interesting light on the conditions which Strauss was now in a position to assume for the performance of his new symphonic compositions.

One is strongly reminded of the parallel passage in Smetana’s symphonic poem Vltava, an exciting moment in a popular work which Strauss must certainly have had in mind. The snapping figure from Ex. 5 builds up in unison on the strings until it finally overwhelms the receding horncalls, and with a burst of rich orchestral colour the mountaineers plunge into a wooded part of their climb. The instrumental tones deepen as thick foliage obscures the sunlight and a new meandering theme appears on horns and trombones:

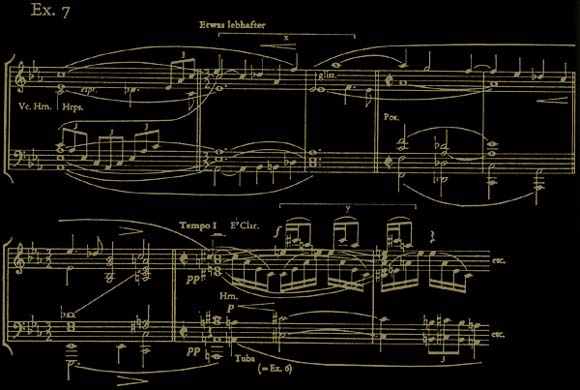

Against a continuously rustling background this new melodic idea alternates with the marching first subject, while fragments of further new motifs enter surreptitiously either as melody or birdsong during the course of some typical modulations:

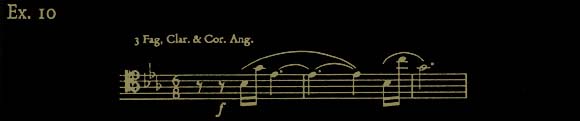

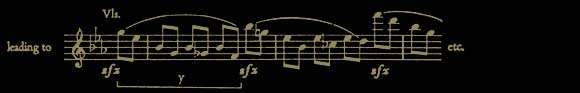

The Mahlerian bird-call Y appears here as only one of a succession of different birds which contribute to the Murmurs of Strauss’s Forest. Later, however, it acquires considerable motivic importance, during which it is handled in a way strongly suggestive of yodelling (see Ex. 10 below).

This section also comes to a clearly defined close on one of Strauss s favourite cadences of shifting tonality, and a development section begins with a quiet return of the marching theme, Ex. 4, now played smoothly by the strings with only the softest background of lower woodwind. The climbers are at an agreeable part of their journey and Strauss too takes it comfortably, contenting himself with inventing agreeable polyphony. The orchestral treatment of these counterpoints varies from a solo string quartet to the full string orchestra with doublings of different degrees on groups of woodwind. Yet in a curious way the effect is like that of an organ and a strong impression is given of Strauss himself sitting at the console improvising while adding different stops on the Swell manual as the mood takes him.

In course of time the mountaineers come to a stream— nothing is omitted from the entire range of Alpine scenery— and Strauss adds the appropriate rushing passage—work to the texture. The motivic interest, however, continues to lie with Ex. 4, though block chords similar to Ex. I— the theme of the mountain itself— can be heard rearing through the polyphony. The suggestion is clearly of ever higher cliffs surrounding the stream, and indeed before long a spectacular waterfall is reached. Here Strauss is in his element and the orchestral treatment lacks nothing in brilliance. After a few bars, beneath the glittering instrumental writing, fragments of an ingenuous little melody can be distinguished, presented phrase by phrase on the oboes.

Strauss adds the heading Erscheinung (Apparition) at this point and we are to imagine the Fairy of the Alps appearing beneath the rainbow formed by the spray of the cascading water. This popular superstition of an Alpine Sprite, which dates back to ancient times, was used by Byron (though he referred to her as a witch) in his great poem Manfred, and Tchaikovsky had already chosen to represent this same vision musically in the scherzo of his Manfred Symphony.

Brief references to Ex. 5 occur from time to time on the horn, suggesting, perhaps, attempts on the part of the climbers to struggle nearer to the glorious apparition. Gradually, however, the irridescence fades and a new melody pours out on the horn and violas, strongly reminiscent, as is well known, of the Max Bruch G minor Violin Concerto (3):

The music then passes into the next section in which the members of the party find themselves ‘on flowering meadows’. Their easy progress is outlined by Ex. 4 on the cellos while the meadow is suggested by soft, high chords on the violins, against which pin-points of colour on woodwind, harps and pizzicato violas provide the flowers. This kind of orchestral pictorialism amused Strauss, who made the extravagant claim in a conversation at about this time that he could, if necessary, describe a knife and fork in music.

The climbers do not linger in these amiable surroundings but press on (Ex. 9 combines melodically with the walking tune, Ex. 4) and quickly reach the Aim— the high verdant pastures on the mountain slopes where Alpine herdsmen put their cattle to graze during the summer months. Strauss accordingly introduces cowbells into the score, and so apt is their appearance that one might think this to be their first employment in the symphony orchestra. Surprisingly enough, however, Strauss took the idea from Mahier’s Sixth Symphony, in which they are used with magical effect but entirely without programmatic significance, a device which Webern also incorporated into his Five Orchestral Pieces, Op. 10.

(3) This is not the first time that the ever popular concerto found an echo in Strauss’s work (see Vol. 1, pp. 13 and 18 Specht, on the other hand, belittles the similarity, claiming on the contrary the strong Straussian flavour of the melody and drawing an especial connexion with the song ‘Anbetung’, op. 36 no.4 (not Op. 37, as he cites). The idiomatic parallel is undeniable but his conjecture of a deliberate allusion on the grounds of the words ‘Ah, wie schon’ (‘how beautiful’) seems more like special pleading.

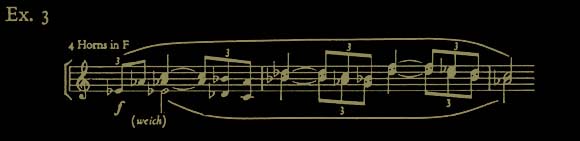

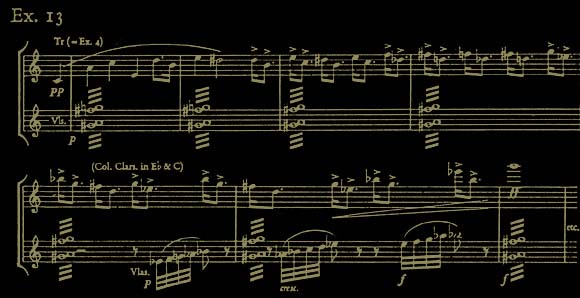

The idyllic calm and beauty of these pastures is conjured up most poetically by Ex. 3 alternating with a new motif derived from the bird- song Ex. 7 (Y), but now transformed so as to suggest yodelling or a herdsman piping (4):

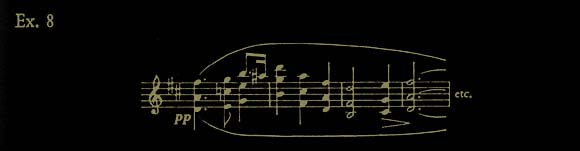

A new and startling theme is screamed out abruptly by the woodwind;

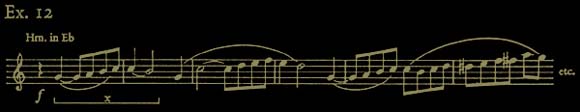

after which the horn introduces yet another new idea, this time a lovely flowing melody suggestive of soft undulating slopes:

Ex. 12 is immediately developed in an elaborate contrapuntal passage of shifting chromatic tonalities during the course of which it is joined by the two earlier climbing themes, Ex. 4 and 5 The party has left the correct path and has got into difficulties trying to retrieve the error by cutting through the undergrowth. The tempo hurries forward as the mountaineers become more and more desperate until suddenly they

(4) The embellishments of trills and flutter-tonguing throughout this section of the score show that the composer of the ‘Sheep’ Variation of Don Quixote has not lost his skill.

push clear of the entanglement and find themselves on the glacier. The brass declaim the chordal motif of the great mountain itself which has suddenly appeared once again in all its grandeur and, inspired and invigorated, the climbers press forward over the ice—field with a tremendous surge of Ex. 4 and 5 For a time the rippling semi-quaver figure of the stream can be heard beneath the stark statements of the rugged fanfare— like Ex. 5 perhaps denoting the waters gushing from beneath the edge of the glacier. Before long, however, these die away; there is a mighty upsurge of Ex. 4 and of the sweeping cadence [Z] of its closing bars, the music fades completely and fragments of Ex. 5 are left tentatively jabbing over a soft drum-roll. Chromatic figures on pizzicato strings add to this passage which is headed ‘Dangerous moments’, and the idea of insecurity is cleverly suggestcd in the fragmentary nature of the texture. The jagged theme, Ex. 5 in particular receives extraordinary treatment on the trumpet and upper clarinets shortly before the summit is reached.

The conquest of the peak is of course the comer-stone of the work and might have been expected to have evoked a splendid orchestral climax, in the construction of which Strauss, of all composers, had long specialized. But whatever his faults Strauss rarely succumbed to the obvious; although some climax of achievement there certainly is (built out of the closing bars of Ex. 5), the orchestration is very restrained as the trombones declaim the Peak motif, a typical Macbeth-Guntram-Zarathustra Naturthema:

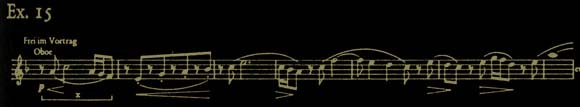

The sounds then fade right away to a soft violin tremolo, beneath which the oboe stammers out a strange hesitant utterance:

The effect is weird and unearthly; the climber seems transfixed by the spectacle which greets him on the actual summit. Indeed it is at first scarcely possible to take in the grandeur of the scene for the utter—even appalling—desolation. Only gradually, as realization of the overwhelming beauty of the view from every side takes the place of this profound sense of awe, does a surge of warm orchestral colour infuse the music. The oboe solo, Ex. 15 of which there are two extended sentences, is directly taken from the startling and graphic utterance of the woodwind, Ex. 11, which had plunged so steeply from the extreme heights as to suggest the precipitous appearance of the mountain side (cf. the note formations of the two respective phrases marked [X] There is in fact a temptation to attribute the birth of both these themes to an attempt at outlining in the very notes the visual impression of the mountainous profile. (In the same way in more recent years Villa Lobos based an orchestral composition on the famous New York skyline by plotting the skyscrapers onto graph—paper.) Certainly if it were so, and the idea is by no means inconsistent with Strauss’s other sources of inspiration for this work, Ex. 15 might well be as true to the view from the summit as Ex. 11 would be of the giant rock-face.

The Naturthema Peak motif, Ex. 14, rears up once again on the trombones, the opening chord-formation of the mountain theme, Ex. 1, is declaimed in a bright C major tonality, and the horns pour forth the second Apparition theme (Ex. 9) followed enthusiastically by upper strings in a broad unison. This time, however, the shape of the theme— and especially its continuation—is different, recalling an earlier passage from the Woodland section, Ex. 7(x).

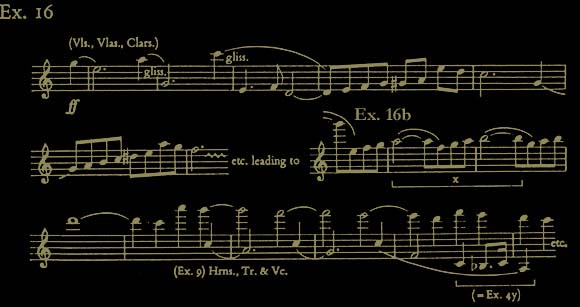

This outpouring of glowing melody is, of course, the long-awaited emotional climax of the Symphony and leads to an impressive C major cadence which is rendered even more emphatic by the mighty cadence of the rock theme, Ex. 5. The effect is comparable with the centre—point of Ein Heidenleben, as is also, to some extent, the style of the continuation. Here is undoubtedly the moment for formal reprise, but, as in the earlier work, Strauss is enjoying himself too much to fall back on conventional devices. The Sun theme, Ex. 2, streams out in combination with the Summit motif (Ex. 14) and with a new cantabile countertheme supplied by the horns and cellos. This in its turn embodies a development of the little figure, Ex. 16(x), the latter sounding more and more like a familiar theme from Wagner’s Meistersinger, especially during its treatment in diminution. The polyphony now becomes more elaborate with much rapidly flowing figuration accompanying a return of Ex. 3, the warm triplet horn theme which has not been heard since the climbers’ brief idyll on the Alm, the high pasture-land.

The tonality shifts to F sharp, and a somewhat stark section begins entitled ‘Vision’. It is as if Strauss has been trying to scan downwards into the far—off green valleys with his binoculars, but now raises them to the gaunt scenery at eye level. The peak motif and the second Apparition theme (Ex. 14 and 9) are combined in a weird development section which gradually incorporates many of the main subjects of the Symphony. The flowing passage-work, Ex. 12(y), and the Meistersinger-like Ex. 16(x) enter together followed by the Sun theme (Lx. 2) and the majestic chordal Mountain theme (Ex. 1), all of which material alternates, appears and reappears in this fascinating central working—out section.

The profusion of trils (often every note of a quickly-moving passage is supplied with a trill), the addition of original and irrelevant counter—points of deceptive interest, since they prove to be non—motivic and unimportant, and the unthinking virtuoso writing for the brass, combine to make this unemotional piece of symphonic construction oddly arresting.

Amongst the new material lavishly spread over the pages of score by the ever fertile and resourceful Strauss (extended melodisings on oboe and horn, elaborate arpeggiando passages for harp, jagged note-formations with sweeping up—beats for the united violins of the orchestra, and so on), a strange, chromatically-rising sequence on the full woodwind band proves to be of more than passing significance. Indeed, at its return a little later it is reinforced not only by strings but by additional desks of flutes, oboes and clarinets held hitherto in reserve and instructed to double with their regular colleagues in any large—scale orchestra employed for performance. The entry of these further forces to the already gargantuan instrumentation coincides with a particularly shrill statement of the Sun motif on four trumpets, followed closely by the first entry of the organ, supplying a deep pedal point in unison with two tubas (5). The chromatic ascending figure suggests a rising heat below which the Mountain theme (Ex. 1) is declaimed by the brass at full strength, and in the original key of B flat minor. The sense of fulfilment is complete, the recapitulation has begun, and the structure of the symphony has, in Bruckner—like manner, found its logical climax.

There is an abrupt change of mood. The murmuring and shadowy scales of the Symphony’s opening are reintroduced to suggest the formation of mists rising up the mountain side. As before, this leads to the Sun theme (Ex. 2) but now given in strange colouring mixed with organ reeds. Gradually the sun is becoming obscured by the gathering haze and an oppressive stillness pervades the atmosphere. This is perhaps the most brilliantly clever section of the work; Strauss has caught with remarkable success the uncanny moment in the mountains when the weather is just beginning to break. In a section described as ‘Elegy’ veiled entries of the Sun theme alternate with a new idea, the setting of which (muted strings in unison against shifting harmonies on the organ) ideally evokes the uneasy calm before the storm.

Over an ominous drum—roll the stammering theme (Ex. 15) is heard again, though no longer on the oboe and devoid of its supporting shimmer of the major triad. Clarinct, cor anglais and bassoon begin it in turn, but each time it tails away, either into fragments of the wailing Ex. 17, or into total incoherence. The oboe itself pitches repeated but irregular groups of staccato high D flats into the rarified air with extraordinary effect. There is a strange interjection from a high clarinet like the cry of some bird of prey. A flash of lightning with a distant roll of thunder (piccolo and bass drum) is answered by the descending B flat minor scale of the Symphony’s opening. As it sweeps with increasing precipitation down the orchestra it leaves its notes behind—again as in the first bars—filling the previously bare canvas with an opaque mass of sound.

A second and far nearer flash and burst of thunder—yet another, this time almost overhead—and rapid scales rush up in the lower strings, in much the same way as Herod’s ‘Angel of Death’ storm music in Salome. Raindrops begin to fall in huge globules (upper woodwind, violin pizzicati and harps) and in a very short time the storm is raging all around.

The great storms of music, Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, Wagner’s Walkure Verdi’s Otello, Britten’s Peter Grimes, all create more than a mere evocation of the fury of Nature let loose. Whether or not the reaction of human beings to the raging elements is to be experienced in the composer’s handling of the scene, thus giving drama or poignance to the climaxes, the form and harmonic structure is always of paramount importance in the creation of a fully convincing programmatic movement.

That Strauss’s storm would overreach every previous orchestral tempest in verisimilitude and virtuosity of descriptive technique was a foregone conclusion. The blinding sheets of drenching rain, the driving wind, the flashing and thundering, all are portrayed with alarming reality, as are the occasional lulls followed by renewed bursts of violence exactly as in real life. Yet, when the tempest has finally spent itself—and it is a long section—it is hard to escape the feeling that, for all his endless resourcefulness and unflagging invention, Strauss has not succeeded in composing more than a clever piece of graphic description.

On the face of it everything seems to be there, including motivic intercst, whilst with engaging skill Strauss couples the storm section with the Descent, thus not only continuing with his basic programme but also thereby pursuing the recapitulation of the Symphony. But although many of the motifs recur one by one, as the sodden mountaineers hastily retrace their steps through one familiar scene after another, they are merely superimposed upon the score and except perhaps for the waterfall, the incorporation of which is a masterpiece of ingenuity, cannot be said to form part of it. The marching theme is heard on the wind-band in inversion (perhaps rather obviously now that the climbers are descending) followed by the rocky motif, Ex. 5, which also descends although it keeps its general outline. In due course the glacier is reached and the appropriate slippery music of the ‘Dangerous moments’ section passes across the score. This rapidly gives place to the pastoral, yodelling music and this in turn to the flowing melody, Ex. 12, giving the impression not unlike that experienced by H. G. Wells’ Time Traveller on his headlong returnjourney from the future to the present. The meandering woodland theme of the lower slopes follows (Ex. 6) after which a tremendous new onslaught of the storm brings in its train a mighty statement of the inverted marching tune now in augmentation on tubas and trombones.

But the storm has almost passed, and the sheet rain gives way once again to the heavy drops, portrayed as before by pizzicato violins and high woodwind, though without the harps. One last flash, a final thunderclap, and the section is over. Solemnly the brass declaim the great Mountain theme, Ex. 1 the climax chord of which is capped by the full organ, (5) an effect which was used before by Strauss in a similar context during the opening passage of Also Sprach Zarathustra. As in the earlier work, the addition of the organ suggests, with considerable power of evocation, the stern beauty of mountains, devoid of life and symbolic of Nature in her severest aspect.

With the re-emerging of the mountain into full view the Symphony’s coda has begun, and the remainder of the score has the wistful nostalgia which Strauss knew so well how to conjure up. There are three sections to this closing portion of the work: Sunset, Auskiang, and Night. Against the specific depiction of the slowly setting sun (widely spaced out descending phrases of the Sun theme, Ex. 2) a solenm Chorale—like melody is enunciated by the brass and harps, while against this in turn the violins pursue tortuous passages derived partly from the ‘Elegy’ (Ex. 17) and partly from the marching theme, Ex. 4, which in its subsidiary phrase y also provides the basis for the chorale. The sunset reaches a glowing climax after which it dies away into the Ausklang.

There is no literal translation of this word which suggests finality. The passage is a farewell and constitutes to a large extent a reliving of most of the sheerly beautiful moments experienced during the course of the work. It is marked to be played ‘in soft ecstasy’ and the value of its spiritual peacefulness should not be underestimated any more than the very real communication in terms of absolute, though possibly somewhat cloying, beauty. The passage corresponds musically with the ‘Vision’ section of the Symphony’s midway point, much of which, declaimed at the time with great sonority, is now recapitulated in soft colours, albeit richly mixed.

The organ continues at first to play a prominent, even soloistic, part, especially during the last glimpses of the setting sun. The full band of woodwind enters gently with the extended Apparition theme exactly as it poured out during the Vision in a flood of ecstatic melodising (Ex. 16). The continuation, with the after-phrase X, and the Bruch-like original Apparition music, Ex. 9 (the horns still soaring over its high phrases), all make their final reappearance. The melodic flood takes other motifs into its sweep such as the Marching tune, Ex. 4, with all its phrases developed separately both directly and in inversion, and the more tortuous winding sections ofE x. 12. Lastly, after what had seemed the final cadence, the startling Ex. 12 leaps up, spanning as before virtually the entire woodwind range.

(5) This beautiful touch is also a dangerous one on grounds of intonation, for even if the organ is tuned to exact concert pitch (a curiously rare phenomenon in concert halls) a sustained chord still tends to sound flat against the living timbre of the orchestral wind.

The work is essentially over, but Strauss preferred to leave the mountain as he had first shown it, shrouded in darkness and mystery. He therefore extends the broad flow of melody by means of Ex. 4 and 2 (now wholly devoid of their original programmatic significance). Gradually, as the light fades, the music moves away from B flat (in which, like the opening of the exposition, the Auskiang had been firmly established) into B flat minor, in which glcomy key the Symphony had begun and in which it is now to end. The texture, therefore, which had contracted to a single organ chord, opens out again with rising phrases (Lx. 2 inverted) above a shifting and ever deeper bass, until at last the great unison B flat is reached, six octaves deep (not seven—the bottom note of the contra— bassoon is reserved for the last bar). The descending scale is then heard again, exactly as in the opening of the work with each note sustaining to form an opaque mass ofsound. Against this, the brass, still as in the opening, enunciate the theme of the mountain itself. It is night and the giant outlines of the noble mass canjust be discerned in the gloom. The violins softly shape a phrase derived from Lx. 4 which rises and swoops down once more in a glissando to the last note. Much of the Symphony has glistened and glowed, but its final sounds are of total darkness with a deep chord of B flat minor picked out against a string conglomerate in which every note of the scale is present.

The full score of the Alpine Symphony was ready on 8th February 1915, and the premiere was immediately projected for early in the following season. Strauss had resolved to dedicate the work to Count Seebach, the Director of the Royal Opera in Dresden, in token of his gratitude to the house in which the first performances ofno less than four of his six operas had been given. Accordingly, at the Symphony’s first performance on 28th October Strauss conducted the orchestra of the Dresden Hof—kapelle although the event took place in the Philharmonie in Berlin, where Strauss still occupied a position of some authority. Attenuated though it had become, Strauss’s contact with the opera and Philharmonic Society in Berlin was not actually severed until 1918. After his sabbatical years for the composition of Elektra and Rosenkavalier, Strauss had resumed his conducting activities to a fairly considerable extent, including concert tours, festivals devoted to his music in all parts of the world, and opera. Even the outbreak of war did not at first curtail this part of his professional life, which with his enormous prestige he was able to treat in far too cavalier a manner for it to become the drudgery it was to poor idealistic Mahler. The delightful legend has been handed down of performances of Cosi fan Tutte in which Strauss, while conducting from the continuo, as was his invariable custom, amused himself during the recitatives by improvising polyphonic accompaniments containing cross—references to Figaro and Don Giovanni, as well as to his own operas. Together with Mozart, Wagner was Strauss’s favourite operatic composer, of whom he gave a great many performances at this time, particularly of the Ring and Tristan. The latter he knew so well that he conducted it from memory, and the story is recounted that on one occasion he ran amok during the complicated 5/4 passage in Act 3. So chagrined was he at having jeopardized the great work at this crucial dramatic moment that as soon as the performance was over he invited the entire company, singers and orchestra alike, to a huge banquet at his own expense. At such moments he revealed the generous personality which lay beneath the increasingly gruff and ungracious exterior. His conducting technique, admirably professional, had early developed into the undemonstrative and unemotional, indeed almost motionless style which made so strong an impression on all who worked with him, or attended his concerts.

In his fascinating autobiography Fritz Busch wrote:

Strauss conducting shows a strange mixture, peculiar to him, of apathy and masterly directness which is not without an element of suggestion. This style of conducting practically never appears exciting but it can arouse excitement in the hearer. Then there seems to be direct contact with genius.

But the real secret of his success is not betrayed, either by the precise movements of his baton, the balanced economy of his gestures or the calm expression on the face of this tall, well-groomed man.

The first performance of the Alpine Symphony caused little stir in the world. In justice it must be recalled that the event took place in the second year of a world war. Had the Symphony been Strauss’s greatest masterpiece its impact could scarcely have been felt outside Germany for over three years. In the circumstances, Strauss was not unduly disgruntled. In a tone of almost amused surprise he wrote to Hofmannsthal:

I do hope we shall see you soon. You must hear the Alpine Symphony on Dec. 5th; it is really quite a good piece!

And this is possibly a fair assessment. Had it been written for four instead of twenty horns, with the remainder of the orchestra in proportion, the warm beauty of many of its passages, and the intriguing descriptive sections with their virtuosity of orchestral imagination, might well have caused the work to retain a place in the concert repertoire, albeit amongst the lesser works of an acknowledged master. But to mount it is such an occasion that neglect has followed automatically. For when allis said and done, with all its qualities, this last symphonic poem stands at the bottom of the first curve of Strauss’s output thus in the event, performances have rarely been projected, and even more rarely brought to fruition.

Yet it is a naive view which merely rejects the work out of hand, and there have always been (and still are) commentators of the first rank who appreciate and value its unusual flavour and spirituality. Prejudice and disappointment on account of the qualities it lacks (and especially those qualities which elsewhere form Strauss’s strongest artistic contribution) can blind one to the atmosphere of exaltation in the face of Nature’s mystery, which is perhaps the most important aspect of the work. It is in some ways Strauss’s parallel not only to Bruckner but to Debussy’s La Mer in that, almost uniquely in his output, he actually describes his elemental subject from an unpeopled, almost detached point of vantage, despite the ingenuous human framework of its avowed programme. Strauss, still in his mood of spiritual preoccupation after the death of Mahler which affected him more deeply than he cared to admit, wrote that he would like to name his Alpine Symphony the Antichrist, since it represented ‘the ritual of cleansing through one’s own powers, freedom through work and the worship of eternal, glorious nature.

This is all very admirable, but unfortunately the fate which pursued Strauss’s invention when he aimed at Eternal and Absolute Truth has already become clear, and much of the writing is disturbingly prophetic of the direction Strauss’s work was taking. The music is, in fact, too comfortable for its subject. In order to reach Strauss’s high—minded intentions it is necessary to wade through much that is essentially the halfplayful note-spinning of a fluent master. How representative it is of this side of his output is easily seen by comparing it with the other throwouts of this period, Of these the Festliches Praeludium, an inflated trifle, composed for the opening of the Vienna Konzerthaus rn 1913, and the Deutsche Motette, also an occasional work of unprecedented difficulty and complication for 16-part unaccompanied double chorus of mammoth proportions, will be discussed later. On the other hand, of greater importance, if still only a time—marker, is the ballet Josephslegende.

Text from:

Richard Strauss A Critical Commentary On His Life and Works

Volume Two

By Norman Del Mar

Cornell University Press

Ithaca, New York 1969, 1986

Audio examples from:

Strauss Symphonic Poems Royal Scotish National Orchestra

Neeme Järvi

Chandos Records LTD. 1995